Reading philosophy is grueling, baffling, and often frustrating.

Like all disciplines it involves learning a new vocabulary and a set of concepts employed in unfamiliar ways. Unlike many other disciplines, authors often refuse to provide a glossary or signposts for the reader. Instead, the journey through the text is akin to a journey through a forest at dusk without a guide.

The payoff is that often (in the glorious undergraduate years where everything is new), then occasionally (as you become socialized into a discipline), you emerge from weeks, months, or years of contemplating the trees and see the forest anew.

Richard Rorty’s Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature showed me that some philosophical problems could be dissolved rather than resolved. Edward Said’s Orientalism introduced me to ideology and how the “Orient” which pervades Western culture is bound up in imperial power and interests. Catharine MacKinnon’s Toward a Feminist Theory of the State demonstrated how an analysis that starts from sex-based domination and exploitation can help us understand many of our institutions. James C. Scott’s The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland South-East Asia revealed how it is possible to not see like a state.

I had a similar revelatory experience reviewing Enrique Dussel Ethics of Liberation: In the Age of Globalization and Exclusion for Marx & Philosophy Review of Books.

One of the most telling indications of the Eurocentrism of philosophy and political science departments in North America is that it is possible to earn a PhD in political philosophy or political theory without ever having heard of Enrique Dussel, one of the founding members of the Philosophy of Liberation and author of over fifty books including The Philosophy of Liberation (1980), The Underside of Modernity (1996), and The Invention of the Americas (1995). (The selection of these three – besides being personal favorites – is due to English translations being available online. Some of Dussel’s major works such as his three volumes on La Política de la liberación are still not available in English.)

In “Eurocentrism and Modernity” (EM) and “Europe, Modernity, and Eurocentrism” (EME) (and many other works), Dussel locates the origins of modernity in 1492. According to a popular myth – what Dussel calls an “ideological construct” of German romanticism (EME 465) – there is a clear line from Ancient Greece and Rome to contemporary Europe. This myth rewrites history placing Europe in the center – most prominently, Hegel sees history as the development of consciousness which culminates with the Germanic Spirit.

Modernity, in Dussel’s view, does originate with Europe, but through a dialectical relationship with its colonies.

Dussel’s restructuring of the Eurocentric history of philosophy puts Spain and Portugal at the philosophical center of modernity, rather than England, France, and Germany:

the concept of modernity occludes the role of Europe’s own Iberian periphery, and in particular Spain, in its formation. At the end of the fifteenth century, Spain was the only European power with the capacity of external territorial conquest, as it demonstrated in the conquest of the Kingdom of Granada from Islamic rule in 1492, the last phase in the centuries-long “reconquest” and colonization of Andalusia. Until that moment, Europe had been itself the periphery of a more power and “developed” Islamic world (just as, until Columbus, the Atlantic was a secondary ocean). (EM 67)

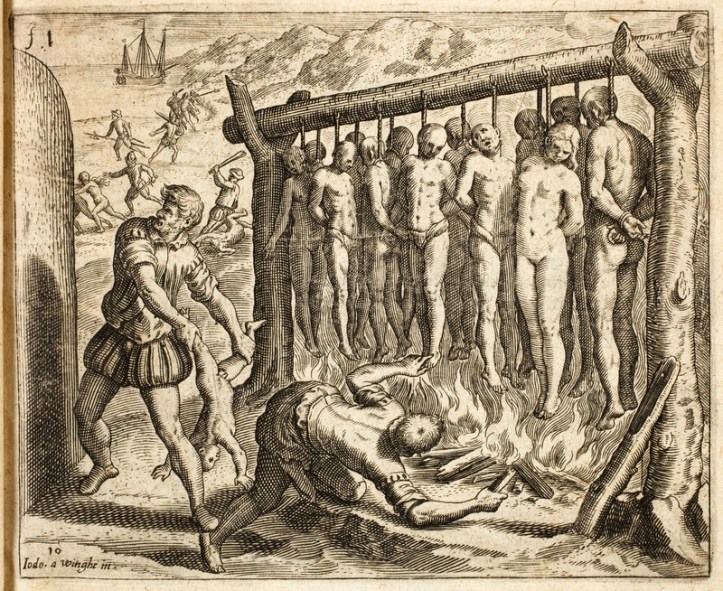

This historical narrative is also an ideology that both justifies and erases colonialism. According to Dussel, “Modernity includes a rational ‘concept’ of emancipation that we affirm and subsume. But, at the same time, it develops an irrational myth, a justification for genocidal violence (EM 66).”

The developmentalist ideology – in which the goal for all groups is to achieve the superior Western, modern civilization – allows for and indeed demands colonialization (a civilizing mission) to educate other groups. Invariably, colonialization involves considerable violence which is justified as a necessary – though supposedly last resort – means of bringing the gift of civilization.

The task, then, is two-fold.

To begin with, there is the criticism of ideology that involves revealing how history has been distorted and reconstructing a history that brings into relief the victims of modernity:

By way of denying the innocence of modernity and of affirming the alterity of the other (which was previously denied), it is possible to “discover” for the first time the hidden “other side” of modernity: the peripheral colonial world, the sacrificed indigenous peoples, the enslaved black, the oppressed woman, the alienated infant, the estranged popular culture: the victims of modernity, all of them victims of an irrational act that contradicts modernity’s ideal of rationality (EME 473).

The other task is rethinking ethics and political philosophy from the perspectives of the “other side” or modernity. This involves making imperialism and colonialism central, but also imagining alternative institutions not based upon domination. This, in a nutshell, is Dussel’s project for a Philosophy of Liberation.

It is an immensely important project. The world is becoming less and less Eurocentric and more multipolar.

The poverty and infeasibility of neoliberal visions of globalization has become increasingly apparent. Political philosophers, if they are to have any relevance, need to imagine a world that escapes the Eurocentrism that still dominates the discipline. Dussel is a leading intellectual and guide in this project.

hermes belts for men

timberland boots

reebok shoes

adidas ultra boost

huarache shoes

michael kors outlet

patriots jersey

adidas tubular

michael kors

nike roshe run

LikeLike